The Cobra Effect

Dear all

This week marked Economics and Business Studies Enrichment Week, and in my Thought for the Week, I explored the idea of unintended consequences, told through the story of a disastrous policy introduced during British colonial rule in Delhi, India.

The story of British presence, control, and eventual retreat from India is – of course – complex and remains controversial to this day. It began in the early 17th Century with the East India Company, a British trading corporation, which established its first trading post in Surat in 1612. Over the next hundred years, the company expanded its influence through trade, diplomacy, and military force, and attempted to establish its dominance through conflict with the local population and other European nations. In 1757, British forces won a major victory at the Battle of Plassey, which secured control over Bengal, one of India’s wealthiest regions.

Through a mix of conquest and treaties with local rulers, British rule expanded, and with it, growing resentment among the population, culminating in the Indian Rebellion of 1857, which was brutally suppressed and marked the formal transfer of power from the East India Company to the British Crown. Queen Victoria was declared Empress of India in 1876.

The city of Delhi played a crucial role in the 1857 uprising. After intense fighting, the British recaptured Delhi, after which it was fully integrated into British rule. By the 1870s, the British were restructuring the city, modernising its infrastructure, and expanding control over its administration.

In charge of the city at that time was Lieutenant Governor William Muir. He was known for his administrative reforms and strict governance and set about introducing various policies aimed at improving public order and economic stability. However, his regime also lacked an understanding of local customs and ecosystems, which sometimes led to unintended consequences.

One of the most pressing issues in the city was the large number of venomous cobras that posed a threat to daily life.

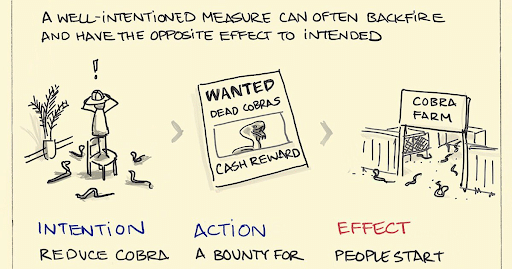

Muir’s solution was to offer a cash reward for anyone who killed a cobra and brought its skin to the authorities as evidence. At first, the plan seemed to work – dead cobras were being turned in, and the population of snakes appeared to be dropping.

But then something unexpected happened. People realised they could make money not just by killing wild cobras but by breeding them. Soon, entrepreneurial individuals began setting up cobra farms, raising the snakes purely for the purpose of claiming the bounty.

Thousands of cobras were bred for this purpose and when the British government learned what was happening they immediately scrapped the reward system. But that wasn’t the end of the problem. Without any incentive to keep the snakes, those who were breeding them released the cobras into the wild. In the end, Delhi ended up with more cobras than it had before the policy was introduced.

This is what is now known as ‘The Cobra Effect’ – when an attempted solution to a problem backfires and actually makes the situation worse. The Cobra Effect is closely linked to another concept – Goodhart’s Law – which is named after Charles Goodhart, an economist who worked at the Bank of England in the 1970s. He noticed that when financial indicators were used as policy targets, they often lost their reliability because people altered their behaviour to meet the targets rather than achieving the intended outcome.

There are lots of examples – one is education. If a school’s performance is measured only by exam results, the content of lessons can become focused only on what is going to be tested, rather than ensuring students receive a well-rounded education.

Another is healthcare: in an attempt to meet targets to reduce patient waiting times, some hospitals have been known to prioritise minor cases over serious but complex ones, leaving those with more serious health issues untreated for longer.

A third example is in business – if a company sets a quota for customer service calls to be resolved in under three minutes, employees are likely to rush through calls and provide worse service, just to hit the target.

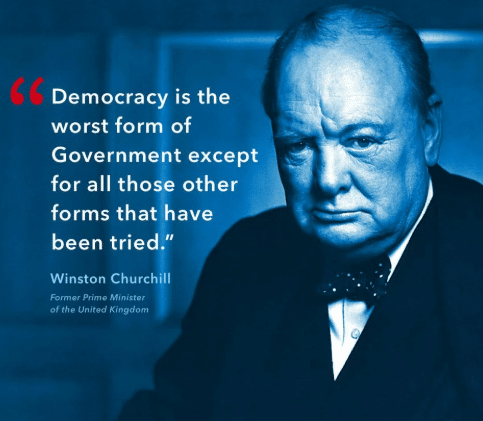

We are all susceptible to creating unintended consequences because we often reach for the simplest and easiest solutions to our problems without thinking about the problems those very solutions might then cause, which are sometimes much worse than the issue we’re dealing with in the first place. In my Thought for the Week, I encouraged our students to avoid this particular pitfall by asking ‘then what?’ when they are about to do something that may have unintended consequences and to remember that on the whole success and happiness in the long run often require taking the harder options in the here-and-now.

Have a great weekend

Best wishes

Michael Bond