Writing English is like throwing mud at a wall – Joseph Conrad

Dear all

There have been many bemused, befuddled, and pithy descriptions of the English language by those who have sought to master it.

Some estimates suggest that English has around 500,000 words, for example, compared to 135,000 in German and around 100,000 in French. While it’s difficult to give a definitive number, it’s fair to say that English has lots of words. It also has approximately 3,500 grammatical rules, many (perhaps even most) of which native speakers follow without even realising they are doing so. Here are just three examples:

Rule 1: The Adjective Order Chain

Imagine describing a knife. You might say: ‘a lovely little old rectangular green French silver whittling knife’, which sounds perfectly normal (if a rather long description). But try saying ‘a green little lovely silver whittling French rectangular old knife’. Suddenly, you sound like you’ve lost the plot. This is because adjectives preceding a noun must follow a strict, unwritten law: Opinion, Size, Age, Shape, Colour, Origin, Material, Purpose, Noun.

Why do we say ‘the big, brown bear,’ instead of ‘the brown, big bear? Because the word ‘big’ (size) must precede ‘brown’ (colour) in the chain. This rule is so ingrained that almost none of us could write the list out, yet native English speakers use it faultlessly.

Rule 2: The Law of I, A, O

Next, consider these pairs of words: hip-hop, ding-dong, ping-pong, and tick-tock. Why do these sound right, but hop-hip, dong-ding, and tock-tick sound wrong? This is governed by a rule called Ablaut Reduplication, a form of reduplication where a word is repeated, but the vowel sound changes. The rule states that when you repeat a word or sound and vary the vowel, the first element must use a higher vowel (from the front of the mouth), and the subsequent elements use a lower vowel (from further back).

Crucially, if there are two words, the first must use an ‘I’ vowel, and the second must use an ‘A’ or an ‘O’. That’s why we have tic-tac, King Kong, and mish-mash. You use this rule constantly: you always say clip-clop, never clop-clip.

This law is so powerful that it can override the adjective order rule we’ve just covered. The Big Bad Wolf breaks the adjective order, but it sounds right because it follows the Ablaut Reduplication rule.

Rule 3: The Animacy Hierarchy

Finally, what about possession? We would usually say: ‘my friend’s bike’ rather than ‘the bike of my friend’? But we don’t say ‘Parliament’s Houses’, we say ‘the Houses of Parliament.’ This is because of the Animacy Hierarchy, which states that the closer the possessor is to being human, the more likely we are to use the apostrophe ‘s’ construction. ‘My friend’s bike’ (human) sounds better than ‘the bike of my friend’, but ‘the ringing of the bell’ sounds better than ‘the bell’s ringing’.

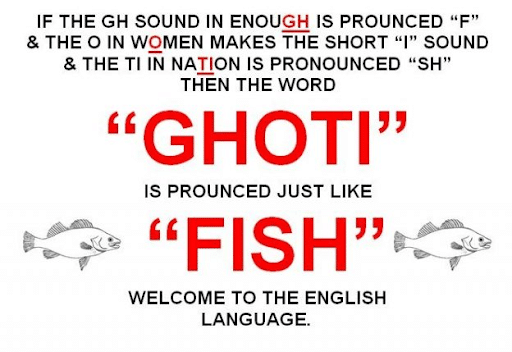

It’s often said that English is both easy and hard to learn – it actually has relatively simple rules of grammar, despite what we’ve just learned; it has a large number of words that derive from other languages, which can make it easier for others to recognise; and our basic sentence structure is often straightforward. On the other hand, there are many exceptions to the way the same words are pronounced; English is full of idioms and metaphors, which can be confusing; there are lots of irregular verbs and spellings that don’t have a clear pattern, which means they just have to be learned; and there are a wide variety of regional dialects and accents.

Those who are studying at Brentwood in what is their second or even third language have my utmost admiration. And for everyone else, perhaps this glimpse into the complexity of our language should give us pause to appreciate its secret genius. Or, as George Bernard Shaw once wrote:

‘I know your head aches. I know you’re tired. I know your nerves are as raw as meat in a butcher’s window. But think what you’re trying to accomplish – just think what you’re dealing with. The majesty and grandeur of the English language; it’s the greatest possession we have.’

Have a great weekend

Best wishes

Michael Bond